Dog training Secret – Progressions and Rehearsals are the KEY!

People tell me all the time, “Well she does great at home, but she’s so bad in public.” Usually, this means a stressed-out, embarrassed owner and a stressed-out, wacky-acting dog. But it doesn’t need to be that way. At the core this is a rehearsal problem, so today we’ll look at how to design a training progression and circumvent the craziness.

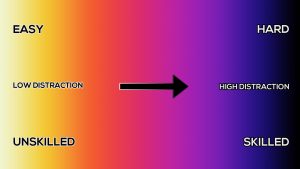

IT’S A GRADIENT

A training progression is a GRADUAL TRANSITION made up of small, practical steps. Here, you see a nice gradient where easy phases into difficult, where low-distraction phases into high-distraction, where unskilled phases into skilled.  This is the optimal training model. This ensures maximum confidence and stability in a variety of situations. However, most people do their dog training abruptly like this:

This is the optimal training model. This ensures maximum confidence and stability in a variety of situations. However, most people do their dog training abruptly like this:  Or not even that, they’ll just go straight for the dropkick like this:

Or not even that, they’ll just go straight for the dropkick like this:  What I see happening a lot is that owners rehearse very little, if at all, and then jump right into taking the show on the road. They start training in highly distracting environments and predictably, this leads to frustration and stress…for both the dog and the owner.

What I see happening a lot is that owners rehearse very little, if at all, and then jump right into taking the show on the road. They start training in highly distracting environments and predictably, this leads to frustration and stress…for both the dog and the owner.

At this point, many owners start applying pressure. They start shouting and reprimanding, and they buy prong collars and head halters, and then they pop and punish and try to force compliance. This increases stress, and stress chemicals both impede learning and act as analgesics—painkillers—which render the pressure less effective, so then you have to apply more pressure, and then you get into this feedback loop of behavior and stress.

Over time this can lead to a whole host of well-documented problems including dependency on the tools, generalized inhibition, residual stress, and even physical injuries. Nobody learns very well like that. You wouldn’t tolerate a boss that did that to you, and you wouldn’t tolerate a teacher or coach doing that to your child.

THINK LIKE A COACH

You can short-circuit this scenario by doing more work on the front end. Understand that changing the picture takes time for the mind to adapt to a new scenario. We want to make changes gradually over time so that the adjustments are small. We help dogs understand how to adapt, help them identify what parts stay the same, and teach them to defer to us if they’re unsure. That’s hard too because most people don’t even really know what to do. This leads us to an inconvenient truth: MOST OWNERS NEED THE PRACTICE AS MUCH AS THEIR DOGS DO!

You’ve got to come at it the same way an athlete would. We don’t teach people how to play basketball at the playoffs. First, they learn fundamental skills in a neutral environment. Here we focus on motor skills, muscle memory, and positive motivation. Then, as they improve, we add new layers, such as working with teammates, playing against opposing teams, and then doing it in front of crowds. This is a training gradient.

And truth be told, there are way more small steps in between that aren’t even represented here. If dribbling was weak or layups were sloppy, those pieces would be isolated and drilled until they were stronger. Only then would they be integrated back into the larger picture.

Any musician, artist, or skilled professional will tell you the same thing. Actors learned it this way, Surgeons learned it this way, and even restaurant servers learned their jobs in a training progression, in a gradient of successive benchmarks.

PRE-PRODUCTION

As we’ve said, many dog owners skip this whole process. This is like learning the game at the playoffs, learning to drive a car on the freeway, or memorizing your lines on opening night! And, remember what we said about using pressure. You can get quick results with it initially, but it’s a superficial success. Usually, you kill their drive and damage your relationship. Pressure isn’t necessary for most pet dogs, and if you do choose to use it, put it at the end. It’s a finishing tool, not a teaching tool. The skills have to be learned and practiced before you correct non-compliance. Remember, we want motor skills, muscle memory, and positive motivation. You only get those through support, encouragement, practice, and repetition. To help you start to visualize this, here’s a basic skeleton for a training progression:

- Cultivate Engagement and Communication

- Develop Motor Skills in a Neutral Environment

- Practice for mastery and muscle memory (these first three are one of our Rules of Three)

- Layer on distractions and/or slowly change the environment

- Shore up weaknesses after changes

- Reevaluate, then Stick with your criteria, Move it up, or Drop it down (this is actually another one of our Rules of Three)

Here are some sample progressions for you to take into consideration:

LOOSE LEASH WALKING

WALKING on leash, as we pointed out, is probably the most egregious example of gradient abuse. People tend to try and teach their dogs in the very environment they have to be pros in. If you’ve followed along this far you know that this is madness.

- First, we need to teach our dogs our communication system and to engage with us with energy. Training should be a fun, problem-solving exercise.

- Then we must teach the requisite skills in a neutral environment, without squirrels, joggers, delivery men, or other dogs. Here is where we work out the kinks. We build muscle memory by getting all the mechanical elements in place correctly. And then we practice a bunch. This doesn’t happen in an afternoon. This is a daily thing for several weeks.

- We gradually layer on distractions.

- We move out onto the driveway for a while.

- Then onto the street in front of the house.

- Then, when your dog is killing it, start taking the show on the road.

If your dog struggles, you go back to a stage where they were more successful and work there for a little longer before attempting a more difficult level again. This not only helps your dog learn more completely what to do, but any training aids you choose to integrate into your system, such as collars, leashes, or harnesses, will be more effective with less effort. And then, you can phase out the training aids instead of them being lifelong dependencies. Remember: it’s not “pressure makes perfect,” it’s “practice makes perfect.”

SIT FOR PETTING

We use similar progressions for challenging behavior like Sit-for-Petting.

- First, we teach the individual motor skills in a neutral environment. The prerequisites are that the dog is already familiar with targeting, sit, and understanding how to work on the leash

- We assemble the components with a neutral, non-reactive helper. Adding a person is stimulating so it would be madness to practice this with strangers. You need this to be someone who can just be quiet and still

- Drill the hell out of it

- Practice in new environments with new helpers

- Ramp up the stakes by layering on distractions

- By now, it ought to be muscle memory so we can start attempting this in other situations

EXECUTION OF THE PLAN

Do you see how this works? It’s gradual. It’s small steps. And it builds in layers. If you try to take a new dog right out into the neighborhood without any rehearsal, practice, or even introducing them to the expectations, you will run into problems. Don’t blame your dog for that; it’s your fault.

Don’t make excuses like, “Oh, she’s a shepherd, or he’s a terrier, or they’re really stubborn.” No. You’re rushing it; you’re forcing it, you’re causing it. Dogs only know what we teach them.

Now, if you’re watching this and are saying to yourself, “Wow, I really screwed up.” It’s not too late. If you’re struggling with something, you can always drop back down and spend time in rehearsals. Break it down into manageable steps and reteach. Get it looking good before moving up to a more difficult environment. Use this rule of thumb:

- Doing just OK, keep practicing where you’re at

- Doing excellent make it harder

- Struggling? Make it easier

NOW GO PRACTICE!

All right, everyone. I hope this has helped get you thinking about designing intelligent and effective training progressions. We have a list of sample training progressions for common behaviors. Check out our Learning Center for all sorts of training secrets (including our Master Keys that reiterate many of these concepts).

Questions for YOU: what are some of the behaviors you’re struggling with? And how has this video got you thinking about your progression redesign? Let me hear from you in those comments.

In the meantime, don’t forget to thumbs up the video. And as always, keep learning, keep practicing, and we’ll see you next time!

I just got an 8 week old Giant Schnauzer, today is our second day together and she is not interested in treats at all yet. Trying to lure behaviors with a rope toy(only thing that gets her attention) is not working out. What’s a brother to do. BoJo & I need your help

PS Maxx Is going for his CGC 7/6/18

Big Doug E

Keep at it, man. Two days is a pinhead on the tip of the iceberg—it’s barely time at all. She just left her litter, she’s in a foreign place, and everything is new and weird. Stress suppresses appetite. As you two bond and she habituates to the new digs, she’ll come around.